|

|

|

|

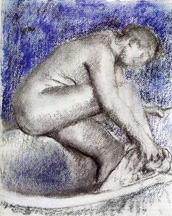

Edgar Degas, "The Bath." 1890-4.

The collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art definitively reinforces the notion that the contemporary work

of Shelley Stefan has a vital connection to the overall oeuvre of the Impressionist Edgar Degas. Stefan's figurative work

sympathetically portrays the intimate, and often sexual, relationships between women and, in doing so, she elevates this historically

overlooked genre to the platform of art. The feminist work of Stefan, no doubt, comes out of a complex historical background

and recently she has been looking towards German Expressionism and, in particular, the printmaking of Kathe Kollwitz (who

is my favorite artist of all time as well.) Much like Stefan's work, one random sampling of Degas' portfolio clearly shows

that he too was obsessed with the female form. While it is blatantly clear that Degas was obsessed with the female form, it

is not clear whether he was a feminist or even if he was, in fact, a misogynist. Most of his closest friends were women like

Louise Halvey, Hortinse Valpincon, Henriette Jeanniot, Julia Braquaval, and especially notable were his friendships with the

artists Berthe Morisot, Suzanne Valadon, and Mary Cassatt. Mary Cassat even went as far as to call him her oldest friend.

As a leading figure of the Impressionist group, Degas must have been clearly reacting against the quassi-pornographic paintings

of academic art that were so often justified in the guise of mythology. In fact, critics like George Smith argue that Degas

was even a Post-Modern Feminist and unlike the rest of the early Modernists, Degas was not interested, at all, in eradicating

the narrative aspect of visual art. Indeed, Degas is a more complex historical figure than he at first appears to be. In the

so-called keyhole portraits of a girl rubbing her feet after a hard day's work, it is hard to say whether the artist is sympathizing

with the subject or coveting her. Interestingly enough, we often have to look outside the image to help us conclude whether

such a portrait of a girl rubbing her feet, or even an image of two women having sex, should be classified as pornography

or art.

Stefan, through her interest in German Expressionism, has recently opted for the powerful effects obtained

through the harsh contrast of black-and-white prints. This is in part due to the nature of printmaking but it is clear that

Kollwitz was able to create a powerful portfolio despite her reluctance for color. As erroneous as it may seem today, nineteenth-century

art theory was immersed in Charles Blanc's contention "Drawing is the masculine sex of art; color the feminine sex."

Degas, being the astute artisan that he was, was very well aware of this fact and as far as color goes, Degas is the undeniable

master. Even Howard Hodgkin, the leading colorist of today, admits his debt to Degas. It is probable that Degas was so prone

to pastels precisely because the medium was the purest form of unadulterated pigment which, therefore, most intensely captured

saturated colors. With his attention to the beauty of the female figure and color, Degas persisted with all of the forms of

beauty that the twentieth-century would completely reject. Even though Stefan's work has often involved color, perhaps her

utilization of black-and-white can play off and deny this archaic notion of color as indicative of the female sphere.

|

|

|

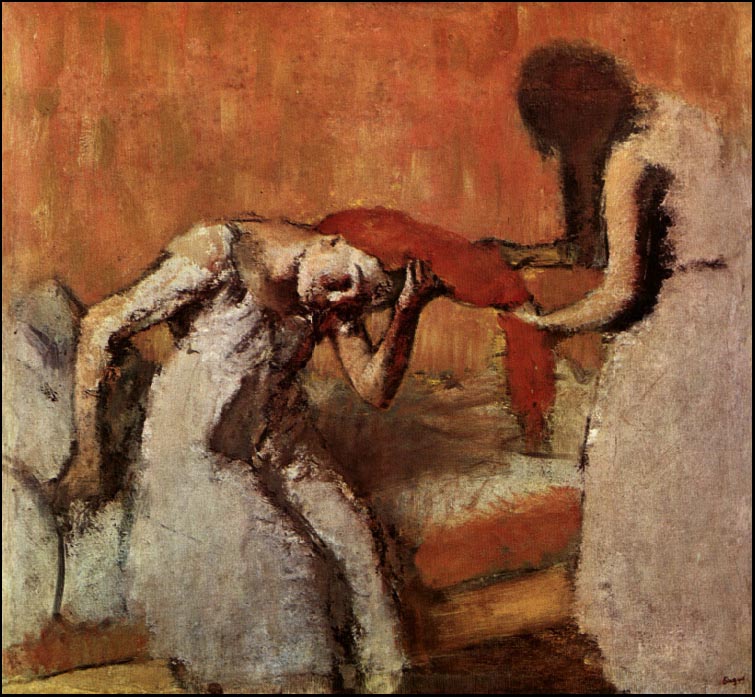

Probably, the most interesting connection between the artwork of Stefan and Degas, though, is their mutual series

on the coiffure or, more simply, the portrayal of haircare. Long hair has often been a feature that socially distinguishes

women apart from men. Sayings such as 'let down your hair' allude to letting loose and not being so constrained to social

formalities. But where Degas focused on women combing their hair, Stefan goes one step further and portrays women cutting

off almost all of their hair. Where Stefan is detailing for the viewer a private moment, it is apparent that cutting off the

hair is, indeed, a complete rejection of the traditional conservative notions of womanhood and, as a result, is a blatant

denial of what Western civilization has deemed as womanly.

Two women grooming each other can be considered an intimate moment. We are given access to these women's

homes and allowed to share in their everyday life. Indeed, the bathing room, where the grooming most often takes place, is

a private realm which is taboo to men. In Degas' and Stefan's images, however, it is difficult to discern whether the viewer

is just one participant among the characters portrayed or if, instead, the viewer is a hidden voyeur enjoying something he/she

should not see. Contrasted to Degas' coiffure images, the action in Stefan's 'Buzzcut 1' is directly in front of you and in

your face and, consequently, you feel more as a participant in the process. This is not the case, however, with Stefan's more

recent work. Often, two women engaged in a sexual act are placed off in the distance, in what seems to be the middle of the

room. Their distance, coupled with the exclusiveness of the sexual act, works to alienate the viewer from the action. We are

not invited to participate and possibly we are not supposed to look for that matter. Nevertheless, the revealing glimpse into

the privacy of the bedroom is the ultimate disclosure of privacy.

|

|

no

Shelley Stefan, "Buzzcut 1." 2002.

Edgar Degas, "Combing the Hair." 1896-1900.

Shelley Stefan. "Toy Series 1." 2002.

|

|

|

|

|

no

Shelley Stefan, "Figuration 1." 2004.

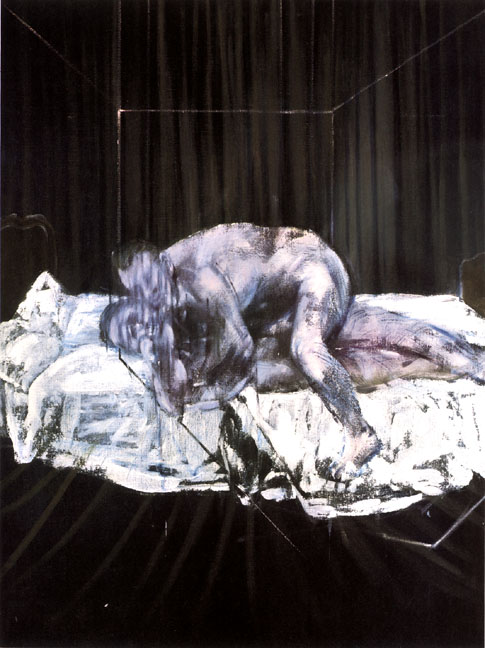

Francis Bacon, "Two Figures." 1953.

Francesca Woodman, "Mirror." 1979.

Collier Schorr, "Wrestlers Love America." 2001.

Robert Mapplethorpe, "Helmut & Brooks." 1978.

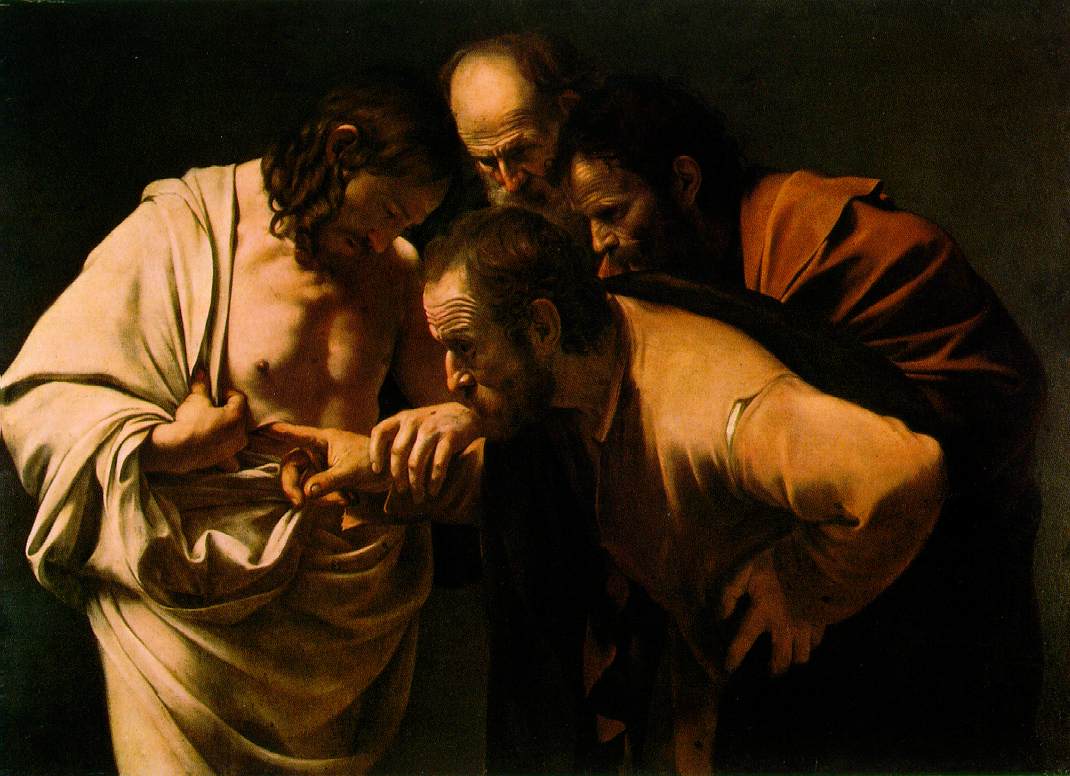

Caravaggio, "The Incredulity of St. Thomas." 1601-2.

|

|

|

|

|

|

With her more recent interest in German Expressionism, Stefan has progressively abstracted her figures more

and more. Taking after the German Expressionists and their utilization of wood's resistant, unpredictable nature to enhance

the unruly nature of their printmaking, Stefan has also adopted the woodcut as one of her primary mediums. Degas' tendency

towards Impressionism similarly also moved him away from the precision of fine visual clarity and towards an abstraction of

the figure that predates Modernist movements in twentieth-century art, as seen in such essential works like Picasso's 'Les

Desmoiselles d'Avignon.' Degas was not as angular as Picasso, though, and his abstraction finds more resonance in obscure

portraiture like Francis Bacon's. Attempting to stay within the vogues of his time, Bacon took on the difficult challenge

of abstracting his subject's visage in a way that was able to retain the idiosyncratic character of the individual's identity.

With Degas, however, it is still in question if he insensitively obscured faces in a demeaning manner that denied the identity

of the subject and worked instead to focus on the reduction of the woman's body to mere visual gratification. Just as confusing,

Degas' technique can also be read as society's reduction of the female's identity. Because the mind is preprogrammed to decisively

read the face down to the most minute details, drawing the human face is, technically, the most difficult task for the artist

and, therefore, any deformity automatically makes the viewer cringe. Even if they are fudged a bit, landscapes and still-lifes

can often be rendered convincingly but when it comes to recreating a visage there is no room for error. It is very doubtful

that Degas was avoiding drawing the face merely for efficiency's sake, but it is certain that he did avoid the gaze of his

subjects at almost all costs. Questionably, the art critic Higgonet defended Morisot's female nudes and how the averted gazes

of her models were refusing to provide the visual pleasure of direct access to the female body. Like Degas and Morisot, Stefan

also persists towards abstraction to enforce her expressive style and her more recent figures frequently deny the gaze to

the audience. Stefan's earlier works, though, fluctuate in the presentation of the visage and she even utilized masks that

work to question identity as well as any subsequent access to that identity. Through her more recent avoidance of confrontation

with the viewer, however, Stefan effectively welcomes and immerses her audience into her world.

While it is evident that Degas was moving away from detail through the slight abstractions of Impressionism,

he was also, at the same time, increasing the depth of his pictures through oblique angles that work to push the viewer's

eye back. These Baroque angles that Degas utilized blatantly denied the flatness that was so often the hallmark of Modernism.

It was due to Degas' interest with the snapshot that led him to embrace the off-composition that was so indicative of his

work as well as the eye-catching vertigo that it subsequently brought. Partly due to her interest in German Expressionism,

Stefan has increasingly flattened her spaces. While this is an inevitable result of the woodcut, her pictures are often logically

composed straight on. Stefan, for the most part, does not draw the viewer into the composition, as much as she creates an

invisible barrier that separates the audience from the main figures. An appropriate example of a Baroque engagement of a homosexual

act, however, would probably be best seen in Robert Mapplethorpe's 'X portfolio.' In the infamous 'X portfolio,' Mapplethorpe

photographed men in explicit sexual acts that effectively enraged Senator Jesse Helms to the point that he denounced the photographs

and called for a public outcry. As Stefan continues to abstract and move progressively away from blatant imagery, it is questionable

whether Stefan wants to now shock the audience or appeal to their empathy.

|

|

|

|

Degas' fascination with the snapshot put him at the virtual advent of photography. Degas' predilection for photographing

women, therefore, either made him a forefather of feminist avant-garde photography or, depending on whom you ask, a forefather

of pornographic photography. Paradoxically, probably both. Feminist photographers like Cindy Sherman were undoubtedly aware

of Degas' keyhole portraits and were reacting against them as a historical precedent. Today, Degas' feminist photographic

legacy can probably be best seen in the work of Collier Schorr. Much like the way Degas inhabited environments of budding

young women aspiring to become ballet dancers (which in many ways, ballet dancers represented what was most feminine in society,)

Schorr similarly goes to wrestling matches where young men attempt to fulfill there masculine roles as aggressive competitors.

Schorr states, "I'm really interested in the similarities between soldiers and wrestlers. The ways in which both fight

as members of a team, but also as sole individuals." By this, much of what Schorr is questioning in her art is how the

individual creates her/his identity according to various categories as sexuality, gender, and nationality. Both wrestlers

and ballerinas simply try to satisfy the ideal that society has imposed on them and it is nearly impossible to cross these

gender barriers without ridicule. Indeed, much like uniformed soldiers, Degas' dancers often seem just like doubles of the

same person - like the artist was simply drawing the same girl but from different perspectives. Schorr admits that she hopes

to create images that represent what her life would have been like if she were born as a boy. It is obvious that the majority

of Shelley Stefan's portfolio is questioning and rejecting the implications of imposed sexual identity in her art as well.

Here I feel it is appropriate to digress to an essay I did about Francesca Woodman in which I compared her art to the

work of Francis Bacon. I feel this passage is appropriate because, in a lot of ways, I feel Stefan and Degas, with their extensive

use of interiors and slight abstraction of the figure, are utilizing the same techniques and tackling the same problems that

Bacon and Woodman did. All of these artists seem to be superficially concerned with the body but are, in fact, working in

psychology. This is where the influence of the word expression comes into play in Stefan's continued interest in German Expressionism.

"The utilization of her own body as a form of art places Woodman directly into the currents of the

Feminist avant-garde that epitomized the Seventies and Eighties. Being an American woman working in the photographic realm

of self-portraiture, Woodman has to undoubtedly draw comparisons to Cindy Sherman, the most prominent artist of the late twentieth

century. However, I feel that Woodman's work is more about the self while, on the other hand, Sherman's self-portraiture is

more often about the social norms that she was reacting against. Consequently, Woodman emerges as the isolated individual

devoid of the fashions of the time. Even though Woodman's nude self-portraiture is clearly about the female form, I cannot

help but feel that the rawness of the physical presentation is transcended by the mental aspects of the overall composition.

Woodman's portraits are often described as ghostly apparitions and perhaps it is this allusion to the spirit that ultimately

dematerializes the body and immerses her work into the realm of psychology. The melancholy facts of her biography that eventually

led to her suicide cannot help but to draw questions of mental disorder as an undercurrent throughout Woodman's oeuvre. Above

all, I feel that it is necessary to compare the apparent similarities of Woodman's photographs with the paintings of Francis

Bacon to help understand the harrowing effects that both of their works conjure up. Both artists are solely concerned with

portraying the human figure but in a way that dissolves the physical form in order to convey its concealed inner essence.

Bacon and Woodman both place their isolated figures in barren interiors that work to suggest interior mental spaces. The figures

are free to move but it feels as if their freedom is relegated to their cell. The lack of detailed props or clothes deny the

viewer any sense of a specific time or place and refocus the eye back onto the main subject. As a result, the artwork doesnt

seem to be solely confined to the present and in the case of Woodman her use of black-and-white photography acts as a relic

of the past but, nonetheless, has an immediacy that brings her world into ours. Woodman's art, therefore, has a peculiar timeless

aspect to it where the spirit of her work will always be able to express her vision for generations to come."

Woodman was a young girl exposing herself to the world, often using herself as her own model and was, hence,

both subject and object. Bacon, however, was often painting the male figure through the eyes of a homosexual male. Im not

sure exactly what that means but you can take what you want from it. Would Degas' images be more powerful if he was a homosexual?

(After all, he never did marry.) It is an interesting aesthetic, as well as ethical, dilemma. But it is here, in Queer Theory,

where Stefan's art surpasses her feminist aspect. Instead of recognizing the differences between the genders, Stefan's artwork

tears them down. In Post-Modern terms, Stefan's message is not so much about either/or as much as it is about both/and. Human

identities and relationships are not as easy as black-and-white and, therefore, they deserve more complex consideration.

Stefan, herself, has noted that the actual creator, as well as the actual audience, of her genre are of

foremost importance. She fears that without the knowledge of the artist's identity that her art may be misinterpreted as merely

some male heterosexual's fantasy. What is this line that separates pornography from high art? Pornography is more common and

is simply utilized to satisfy basic bodily urges, while art, being the pinnacle achievement of human intellect, is always

more difficult to ascertain. Similarly, cooking can be creative but it is generally not considered fine art too because it

aims to satiate base desires rather than enlighten people towards revolutionary action. While there are a lot of factors

involved, what it all boils down to is the intention of the artist, not to mention the intention of the viewer. The art of

Caravaggio announced the advent of the Baroque era but it was only possible through the patronage of Cardinal del Monte who

was basically paying for homoerotic pictures of boys with a deceptive biblical title. In the case of Mapplethorpe's 'X portfolio,'

Senator Helms thought the photographs were pornography while the artworld deemed it art. What made the 'X portfolio' a form

of high art was that it was speaking in a formal language that harked back to the vernacular of Caravaggio in such a way that

promoted the oppressed issues important to the artist. Degas was simply the visual counterpart to virtually every significant

novel of the nineteenth-century which, for the majority, dealt with the tragic social constrictions enforced upon the heroine

as seen in Flaubert's 'Madame Bovary,' Tolstoy's 'Anna Karenina,' James' 'Portrait of a Lady,' Hardy's 'Tess of the d'Urbervilles,'

Hawthorne's 'The Scarlet Letter,' and the emerging writings by female authors like Alcott, George Eliot, Austen, the Bronte

sisters, and Kate Chopin among many others. Whether Degas could be considered a misogynist or not, his images still resonate

and must be addressed in the given context. While we know for sure Degas was an anti-Semite, it is still wrong and egotistical

to completely damn historical figures from the elevated perspective of today's morality. Hannah Arendt frighteningly observed

how 'normal' most Nazis actually were and the need to conform to the social environment, no matter how wrong it might be,

is one of the most defining aspects of human nature. Hindsight is always twenty-twenty and we have to remember that is impossible

for a person to step out of their 'Zeitgeist' no matter how hard they try. Indeed, this is what Stefan's and Degas' work is

about - the ultimate struggle which takes place in the individual between authenticity to her own self versus placing herself

within the social norms of the time.

Thomas Cummins art philosophy

|

|

|

|